The tax break was the latest in favorable legislation for the state’s top political spender.

Image Credit: Wallpaper Flare / Public Domain

By Adam Friedman and Sam Stockard [Tennessee Lookout -CC BY-NC-ND 4.0] –

As Tennessee lawmakers rushed toward the end of the 2022 legislative session, debates over a new school funding formula, the budget, and critical race theory took center stage.

Amid the chaos comparable to the final days of a school year, lawmakers unanimously passed the Tennessee Broadband Investment Maximization Act, containing only one item: a nine-figure tax exemption, primarily benefitting one company.

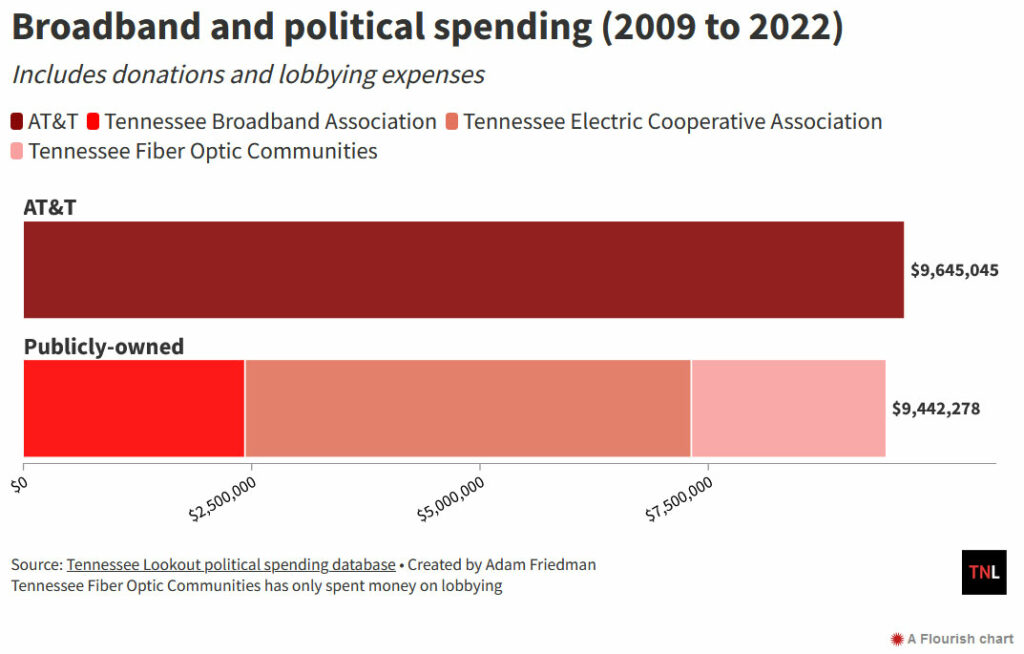

Since 2009, AT&T has spent $9.6 million to influence Tennessee’s state politics, according to a database created by the Lookout. The company, whose significant presence in Tennessee comes from its buyout of BellSouth, is the state’s largest political spender over that period, averaging $500,000 on lobbying and $100,000 on political donations annually.

The act — which went largely unscrutinized by the public, media and lawmakers— granted a three-year sales tax exemption to broadband companies for the purchase of any equipment to improve or expand high-speed internet networks. The annual tax savings, estimated by the Tennessee General Assembly Fiscal Review Committee at $68 million per year, are enough to hire 142 new highway patrol officers, 25 new forensic scientists and build a new park every year.

On its surface, the exemption looked benign. Two years ago, the federal government designated hundreds of millions of dollars to Tennessee to expand broadband in rural communities, and the broadband investment act was designed to prevent those funds from being taxed by the state.

But, Stephen Spaulding, a policy and government affairs executive with the watchdog group Common Cause, said the broadband investment act reminded him of a bait-and-switch tactic to passing legislation.

“You can take a bill, call it Americans for Apple Recognization Day and then just strike out all the language, insert a tax cut, and it will likely pass,” Spaulding said. “There are lots of maneuvers to make something happen without the public having sufficient ways to evaluate who will ultimately benefit or lose out.”

The broad nature of the tax bill and the process of its passage exposed the power of AT&T in the Tennessee legislature, where it has used its money to maintain a vast influence over telecommunications and broadband policy in the state.

An initial draft of the broadband investment act included a provision to remove barriers for nonprofit electric cooperatives to build more high-speed networks in rural areas. But AT&T successfully lobbied for the bill to change into only a tax cut. As the largest private broadband company in Tennessee AT&T is likely to receive the lion’s share of the tax benefit versus the nonprofit cooperatives that are, in most cases, not paying sales tax.

Blair Levin, a former official with the FCC and senior fellow at Brookings Metro, said AT&T likely fears the competition from cooperatives because they have proved a nonprofit model can be more effective in accomplishing the goal of bringing high-speed internet access to rural communities.“The biggest untold story of the last decade is how electric cooperatives have been the biggest primary driver of great broadband for rural areas,” Levin said. “They’ve had the best business model.”

A system satisfying no one

The fight over which companies could build broadband lines and where they could put them has a long and complex history in Tennessee.

It dates back to AT&T’s monopoly over phone lines, passing through the 2015 fight over whether Chattanooga Electric Power Board could bring high-speed internet to Bradley County, and ends up in today’s dispute with electric cooperatives.

The latest battle comes down to whether lawmakers consider broadband a public utility or private good, especially after COVID-19 proved the necessity of high-speed internet in schooling, telehealth and business.

Tennessee’s current broadband policy involves a two-tiered system where private companies operate in profitable urban areas, while publicly-backed companies — like electric cooperatives and municipality broadband providers — function in mostly less prosperous rural areas, with strict rules separating them.

Kathryn de Wit, a broadband expert with Pew Charitable Trusts, said this system creates a situation where competition is low, making prices higher and leading to a lower quality of service.

“The industry is largely a monopoly or duopoly throughout the country, one that’s has been reinforced by some low-grade policy,” de Wit said. “A lack of transparency and lack of information limits our ability to understand whether or not we can create competition in the marketplace.”

COVID boosted broadband as a bipartisan issue

This argument shifted heavily towards the utility side during the COVID-19 pandemic, which in part prompted the broadband investment act.

“Broadband is now an essential service,” said Sen. Jon Lundberg, R-Bristol, who co-sponsored the act.

Lundberg and his House sponsor, Rep. Kevin Vaughan, R-Collierville, brought the bill forward following the passage of the federal bipartisan infrastructure bill which gave Tennessee over $800 million to bring broadband to rural communities.

The two lawmakers sold the bill as a way to avoid having companies pay taxes on federal grants.

“I think this bill was a good idea,” Vaughan said, adding AT&T had no undue influence on the legislation.

But electric cooperatives are more likely than private companies to receive federal broadband funds because they are the organizations expanding into rural areas, and most are nonprofits which don’t pay sales tax.

Representatives from AT&T echoed Lundberg and Vaughan’s sentiments, arguing in a statement the bill was a “wise public policy” decision.

“The moratorium on sales tax on broadband equipment, can help make broadband investments even more effective in connecting people and communities, whether those investments come through private capital or government subsidy programs,” said Scott Huscher, a communications director for AT&T.

Can’t undo the ban

In 2015, the Federal Communications Commission tried to step in and change the playing field between privately-owned and publicly-backed broadband by preempting Tennessee’s ban on allowing publicly-backed broadband from expanding outside their coverage areas.

Republicans in the state legislature decried this as federal overreach, expressing fears that forcing private and public companies to compete was unfair.

The FCC stated its goal was to remove barriers to expanding broadband and create competition to lower internet prices. But, the Tennessee Attorney General sued the FCC, winning in federal court to keep the ban in place.

Since then, the publicly-backed broadband companies have tried to remove the ban to no avail.

Since at least 2009, these groups have funded organizations like the Tennessee Fiber-Optic Communities, the Tennessee Broadband Association, and Tennessee Electric Cooperative Association and spent nearly $9.4 million lobbying and donating to state lawmakers.

Even still, AT&T itself outspent all three groups.

The latest attempt to break the cooperative ban came in 2022 as part of the initial language proposed in the House version of the broadband investment act.

But quickly into the process, AT&T’s lobbyists advocated for lawmakers to cut the expansion provision.

Now, Tennessee lawmakers could renew the tax break as soon as the 2024 legislative session.

Levin, the former FCC official, said this is where lawmakers would ideally step in and analyze the effectiveness of the tax exemption, who it benefited and is it worth it.

“Are lawmakers deciding on a very complicated analysis of if we give a tax break of $68 million, that we lose that money to spend on schools, but we get faster broadband?” Levin said.

That’s what the debate should be, but I’m well aware that in this particular political environment, that does not seem to be the way it’s going.”