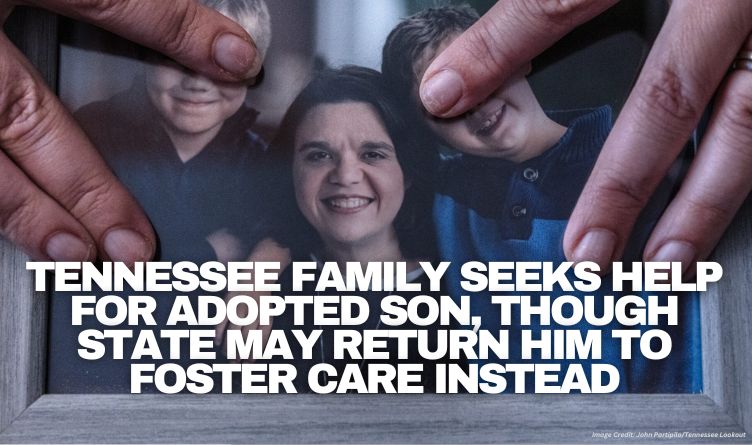

Image: Alisa (pictured at her home in Nashville) and husband Brian face the prospect of having their adopted son returned to foster care and being charged with child abandonment because they cannot get the care they need for his complex psychological problems. Image Credit: John Partipilo/Tennessee Lookout

By Anita Wadhwani [The Tennessee Lookout -CC BY-NC-ND 4.0] –

By the time the 9-year-old boy arrived in their foster home, he had been in the custody of the Tennessee Department of Children’s Services for more than half his life, separated from four siblings and shunted through more than 20 foster homes.

Alisa and Brian said at first they had no intention of adopting the boy, who was around the same age as their biological son.

Six months later, he was calling them “mom” and “dad.” He had behavioral problems: he sometimes hoarded food and wet the bed — nothing Alisa, a seasoned social worker, couldn’t handle. They loved him. With the promise of ongoing adoption support from the state, he was theirs.

Then the trauma their adopted son had endured, including physical and sexual abuse his adoptive mother said he suffered in foster care, began to manifest in ways the couple found increasingly difficult to handle on their own.

He threatened his family with a knife, she said, recounting other incidents: He wrapped an electric cord around his brother’s neck. He headbutted his mother, drawing blood. He exposed himself to other children. He ran.

For the past 16 months, the now 13-year-old teen has been receiving treatment at a Tennessee facility that contracts with the state to provide psychiatric care to children with violent and sexually aggressive behavior. The boy, like his parents, is not identified in this story to protect his privacy as a victim of child sex abuse.

On Thursday, he is due to be discharged against his family’s wishes, according to emails with TennCare reviewed by the Lookout. There is no way to safely bring him back home, Alisa said this week.

Barring intervention, the boy will once again become a ward of the state, an email from the family’s attorney acknowledging DCS’ plans show. Once taken into state custody, the boy would rejoin a system with more than 8,000 children already stretched to the breaking point. Children coming into foster care with complex behavioral and medical needs are among the agency’s biggest challenges, DCS Commissioner Margie Quin has repeatedly told lawmakers over the past two years.

Alisa and Bryan don’t want to lose their son. They said they have spent months trying to find alternatives to get him the care he needs while keeping their other son safe.

“I love him. His entire life has been nothing but chaos,” she said. “And now these terrible systems will continue to damage him even more.”

After meeting with DCS officials to request additional adoption assistance that could help pay for an alternative residential facility or in-home caretakers, DCS notified Alisa and Brian it had initiated child abandonment proceedings against them once the couple made clear they would not be able to pick up their son without more support, according to their attorney, Emily Jenkins of the Tennessee Justice Center.

The proceedings could cost the couple more than their son. Findings of child abandonment would remain on the couple’s record and could also jeopardize Alisa’s license to practice as a social worker.

‘Outside their scope of coverage and not medically necessary’

Child advocates in Tennessee have long cited instances of children being placed in foster care due to a lack of safety net services — a pathway that often begins with the denial of coverage for a child’s complex medical and psychiatric needs by TennCare or private insurance and ends in foster care.

For Alisa and Brian’s family, private insurance for several months split the cost of care at their son’s residential facility with TennCare, which provides secondary health insurance to children adopted from foster care.

In December, the family’s private insurance stopped paying for the residential care, leaving TennCare solely responsible for the child’s medical bills, his mother said.

“By February, Tenncare was already pushing to discharge him, to which I said he was unstable,” Alisa said. “We were still getting reports he had to be restrained.”

By May, Alisa and Brian were shocked to hear that the facility caring for their son intended to send him home, with little follow up care beyond a referral to a psychiatrist who does not accept either TennCare or their private insurance, emails from Jenkins to DCS and TennCare detailing the boy’s care history show.

“They wouldn’t even give him a day pass, because of his behaviors,” Alisa said. “Now they want to send him back with no transition plan whatsoever.”

Citing their son’s need for ongoing care, the couple reached out to TennCare for help, but agency officials declined to cover an alternative residential treatment center, group home or 24-7 in-home aid that could protect both of the couple’s children, the attorney’s emails detailed — services TennCare can make available to children diagnosed with intellectual disabilities who are a danger to themselves or others.

TennCare said these alternative services were “outside their scope of coverage and not medically necessary,” Alisa said, noting her son does not have an intellectual disability.

Alisa also identified an alternative residential care facility willing to take her son, but it, too, fell outside the TennCare insurance network available to the family.

A spokesperson for TennCare was provided a signed release from the family to discuss their child’s care with the Lookout but declined to comment.

“Because this member has engaged legal counsel, we will not be providing comment other than to say it is not accurate that TennCare or the member’s (TennCare managed care organization) has denied treatment or coverage,” the statement said.

“Rather, the provider is discharging after determining he completed treatment and no longer needs residential services,” it said.

The couple turned to DCS to see if they could provide further adoption assistance to help them pay for residential care. The state’s adoption assistance program is designed to provide support to families caring for high-needs adopted children in order to keep them from returning to state custody.

But those meetings led nowhere, Alisa said.

Last week, the family’s attorney reached out directly to Quin, the DCS chief.

“We have been pleading with DCS and TennCare for months to step in and help this family build the scaffolding needed to ensure that (their son) can transition safely back into the community,” read the email from Jenkins.

Without assistance to the family, “he will reenter custody of the very department that placed him in settings where he suffered abuse,” she wrote.

Jenkins received no response, she said Tuesday.

A DCS spokesperson declined to answer questions about the case or whether Quin had directly reviewed it. Provided a signed release form from the family authorizing DCS officials to speak to the Lookout about the case, the spokesperson responded with directions to submit a public records request for the family’s file.

Through their attorney, the family also reached out to the Tennessee Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services for help finding alternatives but have received no offers of assistance from them, either.

“These parents adopted based on the promise of Tennessee that they would have access to services,” Jenkins said. “The people who have abandoned (their son) are DCS, TennCare and the Department of Mental Health.”

“They have been lockstep coordinated in their absolute negligence and abandonment of their duties to ensure that the children in Tennessee get the care they need and avoid entry into a system that DCS acknowledges is not capable of meeting complex mental health needs of children,” she said.

Alisa said her goal is for her son to make a gradual transition back to their home in the future — but only with support.

Child development experts the family consulted at the Vanderbilt University Center for Excellence for Children in State Custody provided detailed recommendations that include a gradual reintroduction to the family through weekend visits, family therapy, in-home services, a safety plan and coordination with the therapist treating their biological son, who was physically abused by his adoptive brother.

Alisa says they have not been offered these options and questions how state agencies will provide care to her son. She also described the pain she and her husband experienced being notified in a meeting with DCS officials that they would be subject to child abandonment charges.

“When I hear about cases where parents are actually abusing children and doing terrible things to them … to be put in the same light is disgusting to me,” she said.

One Response

Bottom line, he’s demon possessed and I know of none who could dispossess him.