Whistleblower flagged possible misuse of grant funds and concerns about how crisis calls were handled.

Image Credit: Rachel Iacovone, Nashville Public Radio

This story was jointly reported by WPLN News and the Tennessee Lookout.

By Anita Wadhwani and Natasha Senjanovic [The Tennessee Lookout CC BY-NC-ND 4.0] –

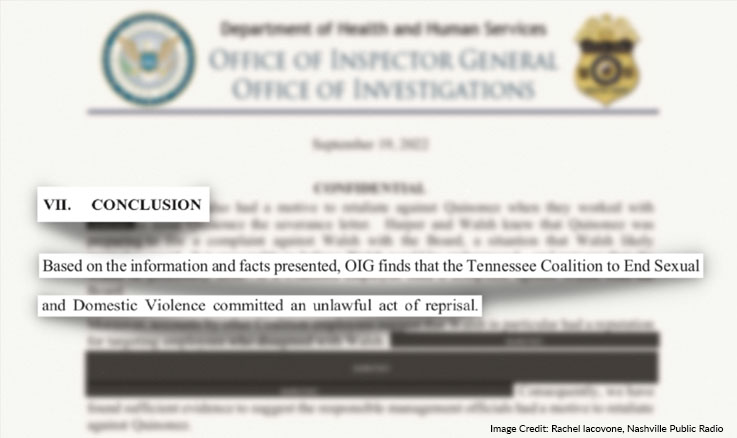

A federal watchdog has found that the Tennessee Coalition to End Domestic and Sexual Violence unlawfully retaliated against and then forced out an employee who blew the whistle about potential misuse of federal funding.

The investigation by the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Inspector General details the experiences of Veronica Quinonez, an employee who was “constructively discharged” in 2019 after she raised concerns with her supervisors, including longtime executive director Kathy Walsh, according to the report obtained by the Tennessee Lookout and WPLN News.

Quinonez’s concerns centered on being forced to answer phone calls from victims, some of them in crisis. It was a role that she said went against the strict rules of the Centers for Disease Control grant that paid her salary.

According to the factual findings summarized in the report, Quinonez was directed to maintain two separate timesheets, one that reflected what she actually did at work, sometimes spending 30% of her time handling calls from abuse survivors and tracking down resources to aid them. The other timesheet showed what she was supposed to be doing under the terms of the $2 million violence prevention grant.

Quinonez said she was not the only employee tapped to take those calls.

“So we (had) people that literally worked on accounting and business and had no knowledge of sexual assault, domestic violence answering these phone calls,” Quinonez said in an interview.

“And I told them that if somebody comes to us who is suicidal and somebody isn’t trained in dealing with a crisis call like that this could be really bad. We might not be able to handle this situation properly. I was told it was about being a team player and everybody had to help out.”

Walsh declined to sit for an interview or respond to a list of questions, and instead joined with the chair of the nonprofit’s board to send a statement disputing the federal findings. They note the Coalition continues to cooperate with the federal government, and said they “look forward to favorably resolving this matter.”

“We are aware of the allegations, but dispute any current conclusions and findings, and intend to fully rebut the same when we have the opportunity.”

The Coalition, led by Walsh for more than 30 years, has built a reputation as the leading voice for domestic and sexual violence victims in the state. It doesn’t provide many direct services, but runs educational programs and lobbies for legislation to combat domestic and sexual violence, among the country’s most pervasive violent crimes.

The report detailing the dismissal of Quinonez in 2019 echoes troubling findings about the Coalition detailed two years earlier, in a pair of state audits released in 2017.

Fear of retaliation

One report by the Tennessee Comptroller found Coalition employees were asked to falsify time sheets and questioned more than $515,000 in accounting procedures.

And an audit by the state’s Office of Criminal Justice Programs, also issued in 2017, flagged complaints of a toxic, or even abusive workplace, with little oversight by the nonprofit’s board of directors. Current and former employees described the leadership and environment at the Coalition as “tyrannical,” “abusive,” “instilling fear,” “manipulative,” and a “fear of Kathy [Walsh],” according to the audit — characterizations that Walsh and the board disputed.

The Coalition took corrective action steps following the 2017 audits and the state hasn’t found significant financial irregularities since.

But the federal report, summarizing events that occurred two years after the state audits, reflects similar complaints about workplace culture. It cited three former employees, whose identities are redacted in the report, who “expressed similar concerns about Walsh’s mismanagement of Coalition staff and reported retaliatory actions toward staff who had questioned Walsh’s directives,” “unhealthy communication patterns,” and that “Walsh was known to be unreceptive toward hearing a ‘critique’ from anyone.”

And it quotes an individual whose name is redacted characterizing the Coalition as having a “toxic environment.”

“Moreover, accounts by other Coalition employees suggest that Walsh in particular had a reputation for targeting employees who disagreed with Walsh,” the report said, in concluding Walsh had a motive to retaliate against Quinonez.

Mel Fowler-Green, a plaintiff-side employment attorney who has no role in the case, reviewed the 17-page report and called it, “a master class of what retaliation looks like in employment settings.” (Fowler-Green serves on the board of Nashville Public Radio.)

The report recommends that whistleblower protection training be required at the Coalition, as well as for federal CDC employees who worked on the DELTA program, which funded Quinonez’s position.

It also recommends backpay for Quinonez, and it left the door open for any “alternative or additional” actions by the federal Department of Health and Human Services.

The OIG report focuses on actions by Walsh and Dawn Harper, the Coalition’s associate director at the time, between May and October 2019, and relies on personnel files, documents, emails, and interviews with staff and board members, including Walsh and Harper.

Quinonez began working at the Coalition in February of that year, as a program manager for a large grant: the $2 million DELTA Impact grant from the CDC, focused on violence prevention. Only nine state coalitions in the country have received what Quinonez calls a “trendsetting, groundbreaking” grant.

Her job was to manage educational programs statewide that teach people how to recognize and stop intimate partner violence.

But by mid-May, the report said, Harper directed Quinonez to begin answering calls from survivors of sexual and domestic violence. The Coalition does not operate a crisis response hotline, but victims often don’t know this.

“When someone calls a domestic violence hotline, most times it’s life or death,” said Carol Wick, an international expert on gender-based violence who once ran a women’s shelter.

Staff who are not trained in crisis response “shouldn’t be taking those calls. Period,” Wick said.

Quinonez initially began answering the calls as she was directed to do, but began voicing concerns to her supervisors about whether spending her time aiding callers violated CDC rules. Guidelines for agencies receiving the DELTA grant, similar to many federal funding sources, require staff to perform only duties related to the grant.

Quinonez was especially concerned about the calls because of the prior 2017 state audit that questioned the Coalition’s timekeeping practices.

“We had nothing to worry about,” Quinonez said she was told, according to the report.

Quinonez told WPLN News and the Tennessee Lookout that it was May 2019 when Harper set up a call with federal grant officials to go over whether guidelines allowed her to take the calls. But Quinonez later told investigators she was specifically instructed “not to speak on the call,” and that it was afterward that Harper asked her to keep two separate timesheets.

In her interview with reporters, Quinonez remembers telling a coworker, “I don’t know what you want to do, but I want to cover my butt. In case this is illegal.” She started requesting everything in writing from her supervisors, and amassed an extensive paper trail that she shared with federal investigators.

Harper declined to be interviewed for this story.

‘The retaliation began’

Tensions rose further over the next three months, as Quinonez continued to take calls. In one week, she spent about 30% of her time handling calls from sexual assault and domestic abuse survivors instead of working on the DELTA grant projects, she told investigators. The calls could be sensitive, time-consuming and, in some instances, require urgent action from staff who lacked training to provide it. That included incoming calls from people who were suicidal. Some of the calls involved outreach to multiple other agencies in an effort to connect victims to necessary resources, she said in an interview.

After she raised the issue to Walsh during a staff meeting, Quinonez told investigators that’s when “the retaliation began.”

In September 2019, Quinonez reached out to CDC grant officials by email with concerns. Then she forwarded their response to Walsh: it said that the Coalition might need to make budget revisions to reflect the time Quinonez was taking calls.

Two weeks later, Quinonez was placed on a performance improvement plan, or PIP, a disciplinary measure taken by the nonprofit agency. That plan directed Quinonez not to communicate with the CDC, although she was their main point of contact for the DELTA grant. It also cited other alleged violations of agency protocols, some of which Quinonez said were never put in writing, however.

Investigators later questioned Walsh and Harper about the process of placing Quinonez on the performance improvement plan.

They offered conflicting accounts, according to the narrative laid out in the report.

Harper said she sought Walsh’s involvement in shaping and reviewing the PIP — but Walsh told investigators she had no role in drafting it. However, emails “show their collaboration,” the report found.

“The facts do not support Walsh’s contentions but do support that Quinonez’ PIP was implemented after Quinonez again brought forth concerns regarding the use of grant funds to pay for activities outside the scope of the grant,” the report said. Inspectors cited the issuance of the PIP as one factor in finding she had been retaliated against.

The situation would soon come to a head.

According to the report, on Sept. 27, a day Quinonez was off work, Harper emailed her with a question about the DELTA grant. Quinonez noted in her response that she was unable to contact the CDC without permission. She went on to explain she felt that the environment at the coalition was “toxic” and that she wanted “nothing to do with it.”

“Needless to say I’m definitely on my way out,” Quinonez texted Harper, according to the report.

She also replied to an email from federal grant officials, noting she was no longer able to respond to them as a result of her performance plan.

When investigators later interviewed the recipient of Quinonez’s email, whose name is redacted in their report, the recipient was “not surprised” by the turn of events. The unnamed federal official reported having previous discussions about the Coalition’s “toxic environment.”

Quinonez reported she continued to call in sick, because the stress from her communications with the Coalition managers exacerbated a medical condition. While she was out, on Oct. 2 and again on Oct. 3, she requested information from Harper about how to file a grievance against Walsh with the Coalition’s board of directors.

Then came a flurry of messages. According to the report, Harper forwarded an email from Quinonez on Oct. 3 about the grievance procedure to Walsh, the executive director, one minute after she received it. Between 10:47 and 10:57 a.m., Harper and Walsh exchanged emails regarding the grievance request. At 10:56 a.m., Quinonez sent a text message to Harper alerting her that someone was accessing Quinonez’s computer remotely and that she was locked out of the laptop. At 10:59, Harper sent Quinonez instructions on how to file a grievance.

Fifteen minutes later — and within an hour of Quinonez requesting information on how to file a grievance with the board — a severance letter arrived to Quinonez’s personal email account, according to the report.

Whistleblower protections

Walsh later told investigators she believed Quinonez’s earlier texts about being “on the way out” constituted a resignation, but an investigator concluded otherwise, noting that Quinonez had followed up to make clear she was not quitting.

The OIG investigator noted that three former Coalition employees, who previously worked on the DELTA grant, “expressed similar concerns about Walsh’s mismanagement of Coalition staff and reported retaliatory actions toward staff who had questioned Walsh’s directive.”

The OIG report went on to say that individuals, whose names are redacted, “questioned Walsh’s lack of involvement in the management of the grant and expressed concerns to Walsh, Harper and [name redacted] about the ‘unhealthy communications patterns’ [redacted] had noticed when asking Walsh to be more involved.’”

The report found that the concerns Quinonez shared with her supervisors about being asked to take calls outside the scope of the grant and allegations of grant mismanagement were “protected disclosures” under federal whistleblower laws.

It found that Quinonez asking how to file a grievance to the board was also a protected disclosure. And it concluded that Quinonez’ departure from the Coalition was “involuntary” — and not a resignation.

Quinonez, the report concluded, had been subject to retaliation by Coalition leaders who had motive to force out an employee questioning their directives to the CDC and members of the agency’s board.

The report also noted that “the evidence reviewed in this investigation suggests that Walsh and Harper have issued PIPs to and constructively discharged other individuals during their tenures at the Coalition,” but did not name those individuals and concluded it had insufficient evidence to assess the circumstances of other former employees.

The report noted that the Coalition’s documented troubles with employee timekeeping gave its leaders reason to be worried that staff could speak up about how funds were being used. And that grants could be taken away.

“Harper and Walsh knew that Quinonez was preparing to file a complaint against Walsh with the Board, a situation that Walsh likely wanted to avoid,” the report concluded. “It is reasonable to believe that Walsh would be embarrassed — and nervous that she would be potentially fired — if a Coalition employee filed a complaint against Walsh with the Board.”

Quinonez did file a grievance with the Coalition’s board on Oct. 3, 2019.

In a response to her on Dec. 18, Chairperson Micki Yearwood said she had appointed a three-member panel of board members to investigate her complaints.

“The Committee finds that there is no substantiation to any of the allegations or many thoughts you have put in your correspondence,” Yearwood said in the written response reviewed by WPLN and the Lookout. “The investigation is closed.”

Quinonez has since left Tennessee, embarking on a new career path of advising other nonprofits on how to prevent harm within their own workplaces.

“I ended up creating my own small business,” she said, “so that nonprofits that do this work are better with their staff.”

View OIG Report HERE.

One Response

Charges and jail time need to follow. Corruption at every level.