The Tennessee Conservative [By Paula Gomes] –

In our story from last week, General Sessions Judge Gerald Ewell, Jr. threatened Tennessee mother Amber Taylor and her daughter saying that he would “send her off” if she did not return to public school.

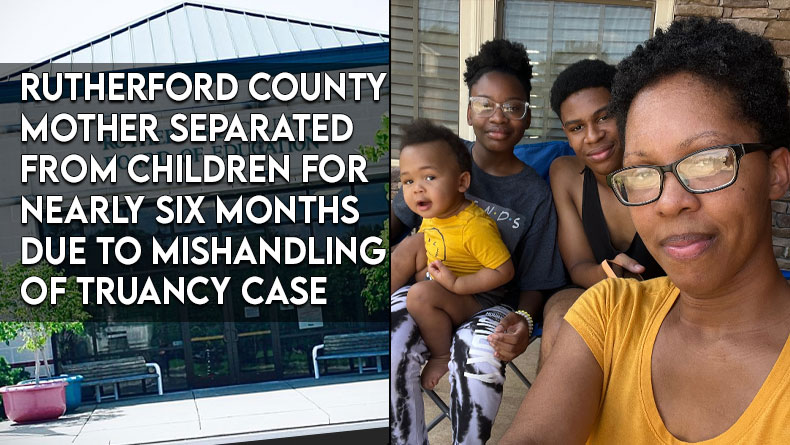

Taylor is not the only parent in Tennessee facing the heavy hand of the juvenile court system on allegations of truancy. Brenda Johnson had two teens in the Rutherford County public school system in January and is also mother to a 20-month old baby.

Johnson’s nightmare began on the Saturday morning of March 4th. The police appeared at her home during a dispute with her twin sister.

Murfreesboro law enforcement cuffed and transported Johnson to the police station to be booked on the Class C misdemeanor of truancy. She was cast into the back of a police car with no shoes and no phone. Her three children were in the home. After sitting in the Rutherford County jail for hours, and handed a citation for truancy, she was set out on the street left to walk seven miles to her home, barefoot.

When she got home late that evening, her children were gone.

When her mother was admitted to ICU on January 1st, 2023, Johnson took her three children and traveled to Georgia. Upon realizing she was not able to leave her mother on January 4th, she contacted the school her teens attended. Two days later, on Friday, January 6th, the school’s counselor responded and suggested that Johnson enroll her teens in the county’s virtual school, which she did.

On Monday, January 9th, Johnson received an email from Gwen Dyer, Truancy Officer for Rutherford County Schools saying that she was scheduling a truancy hearing for January 30th.

On Tuesday, January 10th, Johnson received an email from Jessica Supakhan, Principal of Rutherford County Virtual School rejecting her application. That same day, Dyer told Johnson that she had to return to Tennessee immediately. After Johnson and her children were headed home, Dyer sent another email to Johnson telling her to contact her so that she could give her “other options.” Johnson was back home by the 11th but Dyer kept the truancy warrant for the 30th.

A 2017 state law requires schools to implement a progressive truancy intervention plan that includes three tiers aimed at addressing the root cause of unexecused absences in order to avoid having to refer the case to juvenile court. Under this three tier plan, juvenile court should only be an option after all steps in the plan have been followed and all other means exhausted. This law appears to have been ignored in Johnson’s case.

Under the law, a student who has accumulated five unexcused absences during the school year, and who fails to turn in documentation to excuse the absences “after given adequate time (as determined by the school leader or designee)” will be subject to the school’s progressive truancy intervention plan, beginning with Tier I.

This plan is supposed to be implemented prior to the filing of a truancy petition in juvenile court or a criminal prosecution for educational neglect. At a minimum, this means that the student and parent (or guardian) is supposed to meet with the school, and then have a contract created based on that meeting that will describe the school’s expectations for attendance and additional disciplinary action if the student has further unexcused absences. Follow-up meetings are also supposed to be scheduled to track progress. If that doesn’t work, the school is meant to go to Tier 2, and then Tier 3 before ever getting the juvenile court involved.

Even though the children were already back in school and doing well by March, the response of Rutherford County Board of Education was to prosecute the truancy warrants, a Class C misdemeanor.

Truancy warrants are not against the children, they are issued against the parents. The school can, and does, then issue a juvenile court petition against the child for being “unruly”, what is known as a status offense (not a crime) in juvenile court. Now the juvenile court judge has jurisdiction over both the child and the parent and the power to control them.

On March 6th, the Monday following her arrest, Johnson went to the Murfreesboro Department of Children’s Services’ (DCS) office at 8:30 am to try to find her children. She was given phone numbers for the supervisor, Art Dinkins, and the regional director, Christina Moody. When Johnson finally got Moody on the phone, she said she didn’t have time to take a complaint. Then at 10:10 am, Johnson got a text message from DCS worker Khelsea Smith who told Johnson that she needed to be in court that day at 1 pm.

When Johnson arrived at the juvenile court, she was handed the DCS petition by a sheriff’s deputy. It was full of details about how she had tortured her children and that she had made comments that she no longer wanted to deal with them – allegations that Johnson says are all lies.

In the courtroom, in front of Judge Travis Lampley, she was told she would have a court-appointed attorney named Kathy Baker-Bowen, someone Johnson had never met. DCS attorney Laura Lee Wood, an appointed guardian ad litem (GAL) Betsy Crow, and Johnson’s court-appointed attorney then huddled around the judge’s bench. Johnson was ushered out of the courtroom and told that her children would remain in foster care.

The following day, the foster mother of the children contacted Johnson and told her that she was going to take the baby to Michigan and leave the other two in Tennessee while she attended a family event. Although Johnson did not agree, she was threatened that her children would be moved to another foster home if she refused. While in Michigan, her baby had a seizure and had to be transported to the hospital.

On April 11th, five weeks after the children were taken, Johnson had a short visit with her baby and her 14-year-old daughter. DCS failed to bring her oldest son to the visit.

Johnson’s daughter revealed that the children had suffered mistreatment by the foster family which included the baby being put in a dog cage and a closet. DCS worker Jackson sat nearby busy on her phone and ignored pleas for help.

A series of hearings were scheduled between March 21st and May 18th, but all four were postponed without reason.

Johnson’s first DCS caseworker was terminated in mid-April. On May 1st, a new caseworker, Brooke Moore, prepared a required Progress Report for the juvenile court that was blank, except for the names of the children and parents. DCS had provided no services to Johnson, no services for the children, and the mother had seen only two of her children one time since the March 4th removal.

On May 3rd, a foster care review board meeting was held and Johnson was not even notified. Although DCS knew where Johnson lived, they had the wrong address in their records.

This foster care board review record is dated May 14th, but all of the signatures on the last page are dated June 14th, and the report was not filed with the juvenile court until July 5th, which is when the Mother finally received a copy.

When she went to court on May 23rd, Juvenile Court Judge Lampley set a hearing for July 6th. Johnson, who thought she was having a hearing on June 6th, then found out it was moved to June 22nd. Finally, on June 22nd — 108 days after DCS removed her children from her home without a warrant or a court order — Johnson was finally able to have her day in court. After all of the horrendous allegations against her claiming torture, abuse, and neglect, DCS made their case with the sole witness being Johnson’s 16-year-old son. The day before the hearing, attorney GAL Crow filed a motion for the boy to testify in the secret chambers of the judge so that his mother could not hear what he said. Johnson had four witnesses available to testify about her parenting, but none of them were allowed to speak.

At the end of the hearing, Magistrate Ray White did not find that she had tortured and abused her children but they still did not get to go home with their mother that day. White put in the order that DCS had reasonable grounds to take her children and put them in foster care because she was incarcerated on March 4th due to the truancy charge.

In early June, she was allowed to have another visit with her 14-year-old daughter in a park under the close supervision of OmniVision worker, Keonte Henry. Her daughter was distraught and frightened because she had been removed from the first foster home in May after her disclosures. Her daughter was worried about her baby brother because she was not able to protect him. Her daughter broke into tears telling her mother that she wanted to come home and did not understand why she could not. DCS had told her daughter that her mother did not want to see her. The OmniVisions worker cut the visit short, angry with Johnson for allowing her daughter to talk about the trauma of the separation.

When Johnson heard the terror in her daughter’s voice, she recorded her statements. Instead of investigating the abuse in foster care, her daughter was placed in a secret location and cut off from all contact with her mother. And Magistrate Ray White court-ordered Johnson to destroy the recording, the only evidence she had of her child’s mistreatment.

Johnson was back in juvenile court on July 6th, this time in front of Juvenile Court Judge Lampley on the truancy warrant against her. She believed that the judge would listen to her explain that she had put the children in virtual school so they could remain with her in Georgia to care for her mother. Instead, the judge ordered her to comply with a list of DCS commands.

At the time of this hearing on July 6th, Johnson had no idea what DCS wanted her to do. She had never received a family permanency plan and she had never had a final hearing on whether or not she had abused or neglected her children. When she finally was provided a copy, it contained a litany of demands that had nothing to do with truancy or her temporary incarceration.

Under this plan, Johnson would be policed by the state agency for months, required to provide DCS with proof of her income including copies of her paystubs, provide proof of her housing, allow DCS to make unannounced visits to her home, provide the agency with a detailed account of her monthly budget, complete alcohol/drug and parenting assessments and a psychological assessment, provide proof of transportation including proof of her insurance, and complete a safety child plan.

Up to and including the July 6th hearing, DCS had provided none of these things to her. DCS had never done an unannounced visit to her home. There was never any question about Johnson’s ability to provide housing, food, or transportation for her children. And there were no allegations of alcohol or drug abuse.

Johnson’s nightmare is not over. In limbo under the draconian rule of the Rutherford County Juvenile Court and the Department of Children’s Services, if she fails to do exactly as DCS demands, Johnson stands to lose her children forever under a termination of parental rights proceeding, and be incarcerated by Judge Lampley for failure to comply with his order.

Under state and federal laws, court rules, DCS policies, and even best practices, DCS and the courts have a duty to the children and parents involved. Children are only to be removed from their homes when there is an immediate risk of harm and even then, DCS is required to seek a relative placement to prevent ripping children away from everything they know and placing them in the homes of strangers. Parents are entitled to a hearing within seventy-two hours which examines not only the reason for removal, but a determination as to whether foster placement is the least restrictive environment for the children. DCS is required to provide family planning meetings within thirty days and provide services to parents and children to alleviate the need for removal and reunite the family. Siblings are to be placed together to maintain some stability. And children who want to go home have a right to an appointed attorney who advocates for their position. None of this happened.

Tennessee DCS has faced high scrutiny since its creation in 1995 with constant poor audits, a federal class action lawsuit, multiple commissioners at its helm, and an ever increasing budget. Those who lobby for reform of the system say that just mentioning the agency to state legislators makes them roll their eyes, meanwhile the department’s gross incompetence and damage to children and families continues.

Commissioner Margie Quin was appointed to leadership of the department a year ago on September 1st, 2022, promising a new day in every committee meeting she attended. Along with that promise, she said that a mere additional $156 million in tax dollars would turn things around, and fund the increase of personnel she said was needed to serve families. She got her money, but still the agency is fraying at the seams. Now Tennessee tax payers are shackled to an agency with a billion dollar budget that has the power to enslave children indefinitely.

Johnson’s case is the poster child of systemic failures. Parents have no recourse. Court-appointed attorneys fall on the DCS sword. Juvenile Court judges wield massive power. And guardian ad litems, who know little about the history of the children, fall short of appreciating the psychological despair of separation and isolation.

The last legislators that heard the woeful pleas of continued existence from DCS Commissioner Quin are Senator Kerry Roberts (R-Springfield) and Representative John Ragan (R-Oak Ridge) who lead the sunset hearing December 14th, 2022 and gave DCS six months to report back on its plan to improve the agency’s performance at the June 22nd sunset hearing. Representative Mary Littleton (R-Dickson) has chaired the Children and Family Affairs Subcommittee since January 2019. Children’s advocates say that until these leaders listen to families, nothing will change.

You may contact these legislators here:

Kerry Roberts: sen.kerry.roberts@capitol.tn.gov

John Ragan: rep.john.ragan@capitol.tn.gov

Mary Littleton: rep.mary.littleton@capitol.tn.gov

And DCS can be reached at DCS.Custsrv@tn.gov

About the Author: Paula Gomes is a Tennessee resident and reporter for The Tennessee Conservative. You can reach Paula at paula@tennesseeconservativenews.com.

2 Responses

I don’t understand…why aren’t DCS employees provided with a compliance tick sheet for every case ensuring that each step of the process is met? This sounds like the left hand is not sure what the right hand is doing and is a breakdown of the system at every level. DO BETTER!!

No amount of good intentions can overcome plain stupidity and carelessness. Number one should be the immediate removal of that idiot who professes to be a judge. If his biases are injected into any case, he’s not fit for the job. So far as the school system, we all know that sucks and there’s not much good to be said about Children Services. In both systems their are those who work hard and mostly succeed in spite of the system they labor under. That’s no consolation to those who come up against the fools.