In Tennessee, 48 local and state agencies are partnering with Immigration and Customs Enforcement and reaping financial benefits. (Photo: John Partipilo/Tennessee Lookout)

*Note from The Tennessee Conservative: This article posted for informational purposes only.

By Anita Wadhwani & Adam Friedman [Tennessee Lookout -CC BY-NC-ND 4.0] –

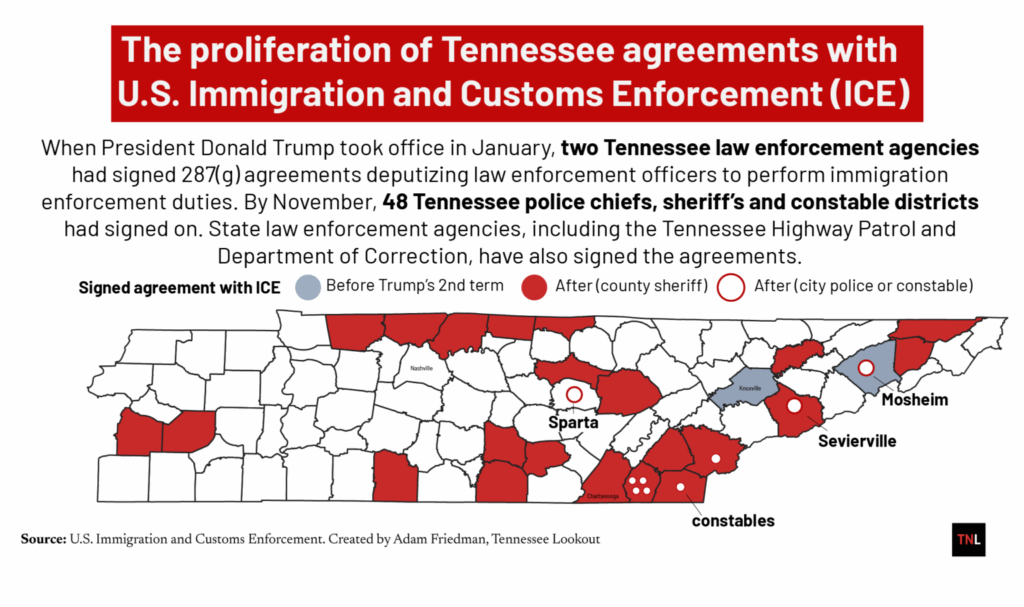

When President Donald Trump took office in January for a second term, just two Tennessee sheriffs had entered voluntary agreements to assist the federal government in immigration enforcement.

Tennessee is now one of a handful of states seeing the biggest expansion of immigration agreements in the nation, along with Texas, North Carolina, Wisconsin and Virginia.

Today, 48 local and state law enforcement agencies in Tennessee have signed onto so-called 287(g) agreements with Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE.

They include 38 county sheriffs’ office, three small-town police departments and five east Tennessee constable districts. Constable districts typically consist of one unsalaried individual who is paid fees to serve warrants.

Two state agencies, the Department of Safety and Homeland Security and the Department of Corrections, have also entered into 287(g) agreements, extending immigration enforcement powers to designated state highway patrol officers and prison guards.

The rapid spread of ICE agreements significantly expands the reach of President Donald Trump’s immigration enforcement and deportation agenda into interior states like Tennessee, where immigrants without legal status represent an estimated 2.2% of the population.

Proponents of the agreements say the force multiplier effect of 287(g) agreements, by enlisting police officers, state troopers, emergency management officials, jailers, constables and prison guards, enhance community safety and more broadly enforce the nation’s immigration laws.

“I decided to do this as there is a right way to enter our country and a wrong way,” said Greene County Sheriff Wesley Holt, who in 2019 initiated one of the state’s earliest existing agreements.

“It is a slap in the face for those who have been properly vetted and went through the naturalization process,” Holt said via email to the Lookout.

But critics of 287(g) agreements have called them an ominous extension of Trump administration tactics in Los Angeles, Chicago, Washington D.C., Memphis and elsewhere that rely on racial profiling to engage in widespread arrests and detentions of immigrants with no criminal records.

Immigrant advocates have long criticized 287(g) agreements for a history of racial profiling allegations, redirecting police to engage in low-level immigration violations instead of community safety and tasking police officers with limited training to interpret complex immigration laws.

“The Trump administration has really converted most of government – Homeland Security and much of the Department of Justice – to do immigration enforcement,” said Lena Graber, senior staff attorney for Immigrant Legal Resource Center, which advocates for immigrant rights.

“Are we just outsourcing all of our local officials to the federal government and its agenda?” she said.

‘Unprecedented reimbursement opportunities’

Tennessee agencies that have partnered with ICE in recent months may have powerful incentives.

ICE agreements in the past have come with no financial compensation beyond training provided by federal authorities and IT equipment allowing communication with federal immigration databases.

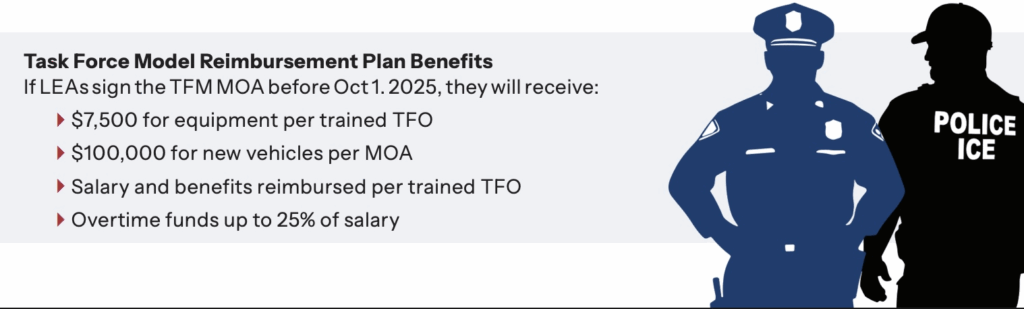

But the Trump administration included $14 billion in federal funding in the Big Beautiful Bill Act in July to fund financial incentives for local and state law enforcement agencies who agreed to ink 287(g) deals by Oct. 1.

They include full reimbursement for the annual salary, benefits and overtime for each 287(g) trained officer, $7,500 for laptops and cell phones per trained officer and up to $100,000 toward the purchase of agency vehicles.

Participating law enforcement agencies are also eligible for bonuses that range from $500 to $1,000 per officer based on meeting benchmarks for the “successful location of illegal aliens provided by ICE and overall assistance to further ICDE’s mission to Defend the Homeland.”

“By joining forces with ICE, you’re not just gaining access to these unprecedented reimbursement opportunities — you’re becoming part of a national effort to ensure the safety of every American family,” Madison Sheahan, ICE Deputy Director, said in a message to potential state and local partners.

In September the Fraternal Order of Police, which represents more than 330,000 officers across the nation, urged police departments to enter 287(g) agreements to take advantage of the unprecedented funding opportunities.

A spokesperson for the Department of Homeland Security did not respond to questions about the amount or timing of potential reimbursements to Tennessee law enforcement agencies.

Memorandum of Agreement documents establishing agreements between Tennessee local and state law enforcement entities explicitly say that 287(g) activities will be carried out at the local law enforcement agency’s expense.

But the agreements establishing so-called “task force models,” which provide the most expansive level of cooperation with the federal government, include an additional clause: “Whether or not the (local agency) receives financial reimbursement for such costs through a federal grant or other funding mechanism is not material” to the agreement.

Dallas Police Chief Daniel Comeaux recently rejected the offer of $25 million by ICE to reimburse the city for the salaries, benefits and overtime of officers who participate in a 287(g), saying the partnership would divert officers from their primary responsibilities. The offer from ICE came with the condition that Dallas officers arrest at least 50 immigrants a day, Comeaux said.

Tennessee lawmakers, in a special session that convened last year, also approved incentives for agencies that partner with ICE, offering $5 million in grants to local law enforcement agencies that enter 287(g) agreements. Questions about the status of distribution of the state funds went unanswered by the Tennessee Department of Safety and Homeland Security.

Small town police to become immigration ‘task forces’

State and local law enforcement agencies can opt to enter one of three different model agreements with ICE.

They include a “jail enforcement” agreement that gives local officials the authority to investigate the immigration status of individuals who are already incarcerated.

A spokesperson for Rutherford County Sheriff Mike Fitzhugh, who faced community pushback when his county’s jail enforcement agreement was made public, stressed the work his deputies did would remain unchanged.

“He is entering a memorandum of understanding with ICE, a continuation of what the Rutherford County Adult Detention Center has done with ICE since 1996,” the spokesperson said. “This memo will allow the deputies to have access to a federal data base.”

Tennessee law already requires local jails to cooperate with ICE officials to verify the immigration status of individuals coming into custody.

A “warrant service officer” agreement allows jailers to serve immigration warrants that authorize the arrest of individuals for civil immigration violations on those in their custody.

The “task force” model gives local and state law enforcement officers powers to enforce immigration law on routine patrols and traffic stops — the most expansive delegation of immigration enforcement powers.

Thus far, 12 Tennessee state and local law enforcement agencies have adopted the task force model, including the Tennessee Department of Safety and Homeland Security, which oversees the Tennessee Highway Patrol.

Other task force agreements with ICE include three constable districts in Bradley County, one constable district in Monroe County and one in Polk County.

Constable districts consist of one elected official who serves as a process server for local courts. They are not required to have police training, but the jobs are often filled by former police officers.

Constables in Bradley, Monroe and Polk Counties did not respond to questions from the Lookout.

The Putnam County Sheriff, the Sevier County Sheriff, Sevierville Police, Sparta Police and the Mosheim Police Department, which operates a force of five people in a town of 2500 in rural northeast Tennessee, has also agreed to serve as a task force agency.

Of the 48 law enforcement agencies with 287(g) agreements contacted by the Lookout, only the Rutherford and Greene County Sheriff’s offices responded.

One Response

GOOD!!