Donald Trump was not the first populist President, and he won’t be the last.

This essay was inspired by a recent visit to The Hermitage.

Published April 5, 2021

Misrule of Law [By Mark Pulliam] –

Tennessee, where I live, has a rich and interesting history.

Admitted into the Union as the 16th state in 1796, Tennessee was originally part of colonial North Carolina. In 1784, when North Carolina conditionally waived all claims to land west of the Appalachian Mountains, the area consisting of what is now known as east Tennessee formed an ill-fated sovereign State of Franklin, which unsuccessfully sought admission to the Union.

North Carolina reasserted its control of the area in 1788, but the difficulties of protecting settlers from hostile natives in the lands west of the mountains led North Carolina to relinquish the lands in 1790, whereupon the federal government recognized the area as the “Territory South of the River Ohio,” or the Southwest Territory.

William Blount, the namesake of the county where I live, was appointed the first governor of the territory by President George Washington. Statehood followed six years later.

Tennessee, which served as a brutal battleground during the Civil War (Shiloh, Nashville, Chattanooga, among others), produced three Presidents during the 19th century (Andrew Jackson, James K. Polk, and Andrew Johnson) and nearly produced a fourth in 2000, Al Gore.

The problem was that the Volunteer State—which Gore had represented in the House and Senate for 16 years (1977-93)–did not support Gore in his freakishly-close race against George W. Bush. Gore turned out not to be a “favorite son” in his home state, with fateful consequences.

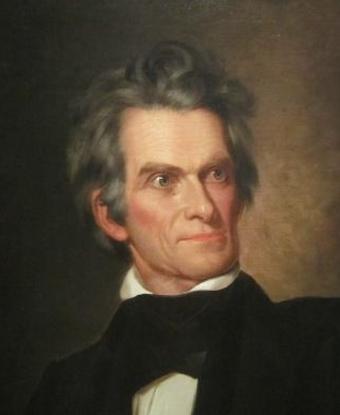

Many famous Americans started their public lives in Tennessee, including Alamo hero Davy Crockett (who represented Tennessee in Congress) and Sam Houston (who served as Governor of Tennessee). But this essay concerns the seventh President of the United States, Andrew Jackson, who had previously served on the Tennessee Supreme Court, in both houses of Congress, and as territorial attorney general.

What brought Jackson national fame and adulation, however, was not his public service but his military prowess, in particular his triumphant victory over the vastly-larger British army, led by General Edward Pakenham, in 1815 at the Battle of New Orleans, bolstered (before and after) by successes in wars against various tribes of native Americans.

Jackson ran for President in 1824, winning a plurality of the popular vote and electoral votes in a four-way race. To Jackson’s bitter disappointment, Congress, selecting the President pursuant to the 12th Amendment due to the lack of an Electoral College majority, chose John Quincy Adams—a result that Jackson believed was the result of a “corrupt bargain” in which fourth place finisher Henry Clay (who was House Speaker) allegedly pledged his support to Adams in return for an appointment as Secretary of State.

Clay may have hoped that the prized appointment as Secretary of State would position him to be the frontrunner candidate for the 1828 presidential election, but “Old Hickory” had other ideas.

By 1828, male suffrage had been extended to most whites, regardless of property ownership. Campaigns became public affairs, and Jackson’s populist message—opposition to corruption by political insiders, adherence to the Constitution, and giving a voice to the common man—resonated with voters.

He won in a landslide, besting Adams by an Electoral College margin of 178 to 83. Following his inauguration in March 1829, attended by many supporters from distant frontier states, he hosted a raucous public reception at the White House. A large crowd of ordinary people descended on the White House, devouring food, quaffing whiskey-laced punch, and reportedly breaking or stealing several thousand dollars’ worth of china. Jackson escaped to his hotel through a window or side entrance (reports vary).

Despite their boisterous behavior at the White House, the unruly crowd was not quelled by armed troops or charged with crimes. Government buildings were not yet considered “shrines” off-limits to the public. Jackson’s exuberant supporters exulted at the election of “the people’s President.”

Jackson did not fail to deliver. Three signature events during his two-term presidency were his veto of re-authorization of the Second Bank of the United States, squelching South Carolina’s threat to defy (or “nullify”) the Tariff of 1832, and removing native Americans from the interior of the United States (a form of border security).

Jackson believed that the national bank was both unconstitutional (refusing to defer to the contrary opinion of the Supreme Court) and unwise as a matter of policy. To Jackson, the bank symbolized how a privileged class of businessmen oppressed the will of the common people of America. His veto message on Congress’s vote to renew the national bank has distinctly Trumpian tones:

“It is to be regretted that the rich and powerful too often bend the acts of government to their selfish purposes. Distinctions in society will always exist under every just government. Equality of talents, of education, or of wealth can not be produced by human institutions. In the full enjoyment of the gifts of Heaven and the fruits of superior industry, economy, and virtue, every man is equally entitled to protection by law; but when the laws undertake to add to these natural and just advantages artificial distinctions, to grant titles, gratuities, and exclusive privileges, to make the rich richer and the potent more powerful, the humble members of society–the farmers, mechanics, and laborers–who have neither the time nor the means of securing like favors to themselves, have a right to complain of the injustice of their Government. There are no necessary evils in government. Its evils exist only in its abuses. If it would confine itself to equal protection, and, as Heaven does its rains, shower its favors alike on the high and the low, the rich and the poor, it would be an unqualified blessing. In the act before me there seems to be a wide and unnecessary departure from these just principles. (Emphasis added.)”

This was an early indictment of privileged elites benefiting from insider access and preferential treatment. He continued:

“Experience should teach us wisdom. Most of the difficulties our Government now encounters and most of the dangers which impend over our Union have sprung from an abandonment of the legitimate objects of Government by our national legislation, and the adoption of such principles as are embodied in this act. Many of our rich men have not been content with equal protection and equal benefits, but have besought us to make them richer by act of Congress. By attempting to gratify their desires we have in the results of our legislation arrayed section against section, interest against interest, and man against man, in a fearful commotion which threatens to shake the foundations of our Union. It is time to pause in our career to review our principles, and if possible revive that devoted patriotism and spirit of compromise which distinguished the sages of the Revolution and the fathers of our Union. If we can not at once, in justice to interests vested under improvident legislation, make our Government what it ought to be, we can at least take a stand against all new grants of monopolies and exclusive privileges, against any prostitution of our Government to the advancement of the few at the expense of the many, and in favor of compromise and gradual reform in our code of laws and system of political economy. (Emphasis added.)”

In other words, Make America Great Again.

Jackson’s showdown with South Carolina Senator John Calhoun (who in the pre-17th Amendment era spoke for the state legislature), who had previously served under Jackson as Vice President, over South Carolina’s threat to “nullify” a federal tariff –and to secede from the Union, if necessary—provoked Jackson into bellicose resolve. When South Carolina passed an ordinance vowing to forcibly resist the federal government’s collection of the objectionable tariff, Jackson warmed to the fight. Jackson once said to Martin Van Buren (who served in Jackson’s cabinet and succeeded him as President) that “I was born for a storm, and a calm does not suit me.” Like Donald Trump, Jackson was a natural pugilist who never backed down.

Jackson responded to the threatened nullification and secession in blunt, undiplomatic terms. Readers used to the milquetoast language used by modern Presidents prior to Trump may be surprised to hear what Jackson had to say via proclamation about South Carolina’s threat to secede:

“I consider, then, the power to annul a law of the United States, assumed by one State, incompatible with the existence of the Union, contradicted expressly by the letter of the Constitution, unauthorized by its spirit, inconsistent with every principle on which It was founded, and destructive of the great object for which it was formed. (Emphasis in original.)”

He warned the people of South Carolina:

“But the dictates of a high duty oblige me solemnly to announce that you cannot succeed. The laws of the United States must be executed. I have no discretionary power on the subject–my duty is emphatically pronounced in the Constitution. Those who told you that you might peaceably prevent their execution, deceived you–they could not have been deceived themselves. They know that a forcible opposition could alone prevent the execution of the laws, and they know that such opposition must be repelled. Their object is disunion, but be not deceived by names; disunion, by armed force, is TREASON. (Emphasis added.)”

Jackson intended to preserve the Union at all cost. He ordered his Secretary of War to prepare to march against South Carolina, if necessary. Jackson told a congressman from South Carolina to deliver this message to his constituents:

“Please give my compliments to my friends in your state, and say to them that if a single drop of blood shall be shed there in opposition to the laws of the United States, I will hang the first man I can lay my hand on engaged in such treasonable conduct, upon the first tree I can reach. (Emphasis added.)”

“Make my day,” he warned (paraphrasing).

Aided by the rhetorical support of Massachusetts Senator Daniel Webster, after Jackson successfully requested Congress to formally approve to employ force if South Carolina obstructed the collection of the tariff in the state, the proponents of nullification buckled. Due in part to a tariff compromise brokered by Henry Clay, South Carolina rescinded the ordinance of nullification. Firmness and tough talk worked. The secession crisis that was to bedevil Abraham Lincoln 30 years later was averted.

Jackson’s most controversial legacy is his Indian policy, especially the Indian Removal Act that he proposed, and which Congress enacted in 1830 following intense debate.

The Act authorized the negotiation of treaties with tribes in the Southeast to induce them to voluntarily relocate westward. Jackson signed over 60 land cession treaties, pursuant to which nearly 50,000 native Americans moved, mainly to present-day Oklahoma. After Jackson left office, the federal government, with assistance from state militias, forcibly relocated other tribes (notably the Cherokee) who had not met a May 23, 1838 deadline. Due to severe weather, disease, and lack of food, the long trek—often referred to as the “Trail of Tears”—resulted in many deaths.

Although the parallel with Trump’s border security policy is imprecise, both Jackson and Trump sought to strengthen American sovereignty by removing noncitizens whose presence was believed to hinder the opportunities and jeopardize the security of American citizens. In his 1830 message to Congress entitled “On Indian Removal,” Jackson explained the basis for his desire to relocate native Americans:

“The consequences of a speedy removal will be important to the United States, to individual States, and to the Indians themselves. The pecuniary advantages which it promises to the Government are the least of its recommendations. It puts an end to all possible danger of collision between the authorities of the General and State Governments on account of the Indians. It will place a dense and civilized population in large tracts of country now occupied by a few savage hunters. By opening the whole territory between Tennessee on the north and Louisiana on the south to the settlement of the whites it will incalculably strengthen the southwestern frontier and render the adjacent States strong enough to repel future invasions without remote aid. It will relieve the whole State of Mississippi and the western part of Alabama of Indian occupancy, and enable those States to advance rapidly in population, wealth, and power. It will separate the Indians from immediate contact with settlements of whites; free them from the power of the States; enable them to pursue happiness in their own way and under their own rude institutions; will retard the progress of decay, which is lessening their numbers, and perhaps cause them gradually, under the protection of the Government and through the influence of good counsels, to cast off their savage habits and become an interesting, civilized, and Christian community.”

“What good man would prefer a country covered with forests and ranged by a few thousand savages to our extensive Republic, studded with cities, towns, and prosperous farms embellished with all the improvements which art can devise or industry execute, occupied by more than 12,000,000 happy people, and filled with all the blessings of liberty, civilization and religion?”

This is an early expression of America First.

Historians often mark Jackson’s presidency as the beginning of an era in American history—”The Age of Jackson.” Jackson’s presidency was also a harbinger of political realignment. The “Democratic Republican Party” became simply the “Democratic Party”; the opposition Whig Party would eventually evolve into the modern Republican Party.

Jackson’s presidency was momentous and transformational. His friend and protégé, Sam Houston, won independence for Texas in 1836.

Sadly, Jackson would not live to see the Lone Star State join the Union as the 28th state in 1845.

Jackson is most closely associated with the tradition of populism—appealing to and representing the interests of ordinary Americans. In this regard, he was the precursor to the tumultuous 45th President, with whom he otherwise has little in common.

Trump, hardly an impoverished orphan who became a military hero, or a duelist willing to shed—and draw—blood to defend his honor, was elected and governed using the same populist themes that resonated with the American people almost 200 years earlier. Trump was not the first disruptive, combative, nationalistic, populist President, and he won’t be the last.

About the Author:

Mark Pulliam writes from East Tennessee.

A Big Law veteran, he retired as a partner in a large law firm after practicing for 30 years.

A contributing editor to Law & Liberty since 2015, Mark also blogs at Misrule of Law.

He considers himself a fully-recovered lawyer.